Passing Through a Small Town

Here the highways cross. One heads north. One heads east and west. On the corner of the square adjacent to the courthouse a bronze plaque marks the place where two Civil War generals faced one another and the weaker surrendered. A few pedestrians pass. A beauty parlor sign blinks. As I turn to head west, I become the schoolteacher living above the barber shop. Polishing my shoes each evening. Gazing at the square below. In time I befriend the waitress at the cafe and she winks as she pours my coffee. Soon people begin to talk. And for good reason. I become so distracted I teach my students that Cleopatra lost her head during the French Revolution and that Leonardo perfected the railroad at the height of the Rennaissance. One day her former lover returns from the army and creates a scene at the school. That evening she confesses she cannot decide between us. But still we spend one last night together. By the time I pass the grain elevators on the edge of town I am myself again. The deep scars of love already beginning to heal.

The Long Road

It’s one of those highways you come across late at night. No signs. No arrows. Just a road running north and south. You pause. You look one way. Then the other. Nothing. Only the hum of the engine, the chirping of crickets confirm you are here. You can’t remember where you’ve been. Where you are going. If it weren’t for the lines drawn through the middle, you’d think you were drifting down a river. Or stumbling upon a path through the sky. Remember, it is a moonless night. You are tired. Hungry. No one to talk to. Afraid that what you were thinking might have come true. You look to your left again. Perhaps you see a mountain. An ocean. A lover you wish you hadn’t lost. Spirits that seem so familiar, drifting in from the dark. You wait in that silence. It may be years before it is safe to proceed.

Trains

I am seduced by trains. When one moans in the night like some dragon gone lame, I rise and put on my grandfather's suit. I pack a small bag, step out onto the porch, and wait in the darkness. I rest my broad-brimmed hat on my knee. To a passerby I'm a curious sight—a solitary man sitting in the night. There's something unsettling about a traveler who doesn't know where he's headed. You can't predict his next move. In a week you may receive a postcard from Haiti. Madagascar. You might turn on your answering machine and hear his voice amid the tumult of a Bangkok avenue. All afternoon you feel the weight of the things you've never done. Don't think about it too much. Everything starts to sound like a train.

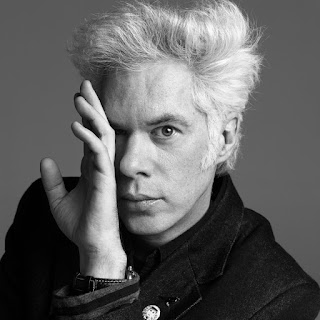

David Shumate is the author of High Water Mark (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2004), winner of the 2003 Agnes Lynch Starrett Prize and the 2004 Best Books of Indiana, poetry category. His second collection of prose poems, The Floating Bridge, was published by the University of Pittsburgh Press in 2008. His poetry has appeared widely in literary journals and has been anthologized in The Writer's Almanac, Good Poems for Hard Times, and The Best American Poetry 2007. He teaches at Marian College in Indianapolis and lives in Zionsville, Indiana.